The architecture of deception: Why you don't control processes, but rather your hypotheses about them

In-depth data analyses often reveal significant discrepancies between the assumption of linear business processes and the operational data reality. Where strategic homogeneity is assumed, structural heterogeneity often prevails at the data level. Ignoring this complexity is not a technical oversight, but a fundamental threat to AI strategies and digital transformations.

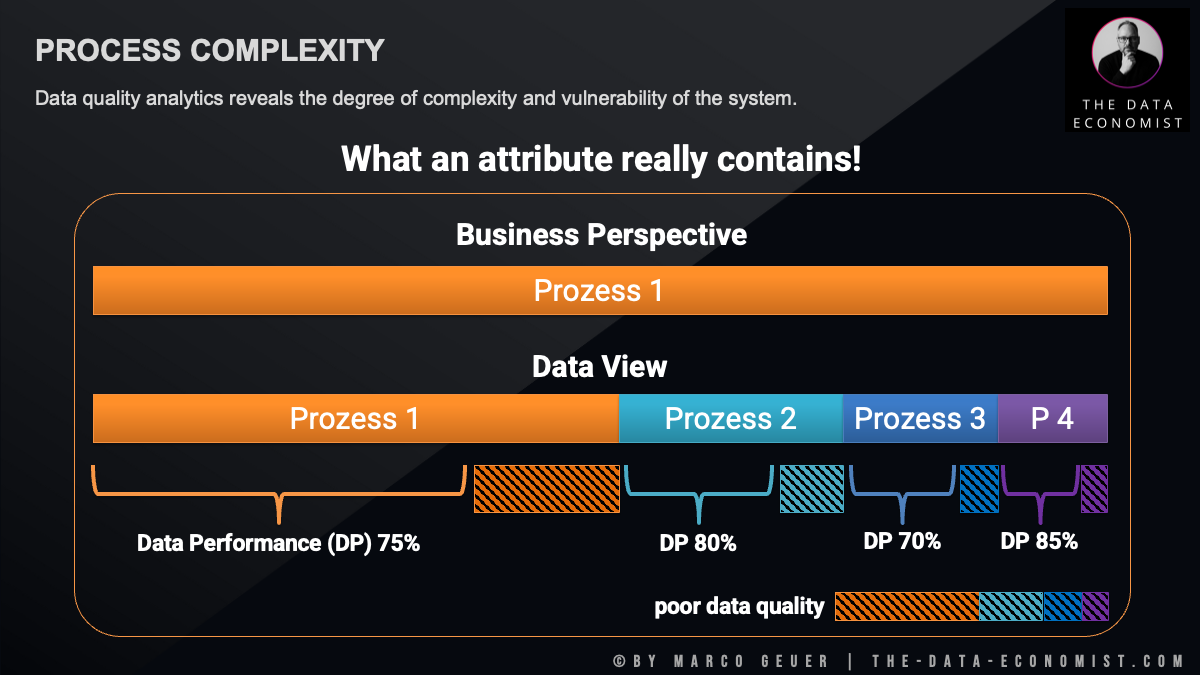

When a C-level decision-maker looks at their company's process landscape, it usually presents itself in reassuring linearity. Take a standard process such as ‘order processing’ as an example: from a business perspective, this appears to be a monolithic block. It suggests uniformity, complete controllability and clearly defined responsibilities.

However, this perception often proves to be a risky illusion.

A change of perspective to a data view often reveals a completely different picture. What is declared as a singular process at the strategic level turns out to be a chain of heterogeneous sub-processes that have been artificially subsumed under the same data attribute. This divergence between the perceived simplicity at the management level and the actual complexity of the data structure is one of the primary causes of the failure of digital transformation projects.

The hidden costs of semantic overload

A thorough analysis clearly demonstrates the consequences of hiding process variance in database fields. A single attribute often acts as a catch-all for various variants that cannot be assigned to a standard category. This ‘attribute condensation’ has far-reaching implications:

- Distorted performance measurement: While management assumes that it is evaluating the success of a homogeneous overall process, it is in fact only recording a distorted average value. The data often shows the following pattern: while the core process runs smoothly, the hidden sub-variants are subject to massive fluctuations in their data-based performance values. Aggregated key figures mask these clusters of inefficiency. Corporate management is thus partly flying blind, as the instruments suggest stability while individual operating units are already showing significant deficits.

- The shadow of poor data quality: Particularly critical is the realisation that each of these hidden sub-processes brings with it its own dimension of data quality deficiencies. Poor data quality in this context is not a random technical phenomenon, but a structural result of complexity. With each integration of a new process step into an existing field, a new zone of uncertainty arises – an accumulation of data noise that makes precise analysis increasingly impossible.

Why AI is bound to fail in this reality

The current euphoria surrounding artificial intelligence, classical machine learning (ML) and large language models (LLM) tempts us to apply these technologies to existing data sets without reflection. However, training prediction models on such fragmented structures inevitably leads to malfunctions:

Algorithms learn from the data perspective, not from the abstract business perspective. They detect the statistical patterns of the hidden sub-processes. However, if such a model is trained to predict parameters of the higher-level business logic (e.g., ‘forecasting the throughput time for order processing’), this results in distorted predictions and poor model quality. The algorithm attempts to learn a statistical regularity for an entity that does not exist as a homogeneous unit in the data. Valid data-based decisions are impossible as long as the database masks the structural fragmentation of the process reality.

The psychology of decoupling: map vs. territory

However, the real problem lies deeper than the data architecture; it is anchored in the mental models of leadership. The most dangerous assumption in modern management is the confusion of taxonomy with reality. While C-level decision-makers look at strategic maps that suggest a world of linear value chains, the underlying data streams document a far more chaotic ontology of the company.

A mental model is not a psychological abstraction, but rather the internal ‘cognitive operating system’ that a decision-maker uses to filter information and define causalities. It is the unconscious assumption about how cause and effect supposedly interact in the organisation.

In practice, this means that managers rarely control the actual processes themselves. They control their hypotheses about these processes.

If the mental model envisages a smooth, efficient pipeline, but the data reveals a fragmented network of workarounds and shadow processes, a fatal strategic disconnect arises. One then manages a phantom image, while the actual value creation remains unregulated. This disconnect is not a technical failure, but an epistemological one. Those who mistake the map (the process diagram) for the territory (the operational data reality) lose the ability to intervene effectively.

Strategic realignment: synchronising model and reality

In order to restore the ability to act between strategy and operational excellence, senior management must proactively synchronise their cognitive maps with the data reality. Strategic excellence today requires a willingness to view the company through the unvarnished lens of the digital trail and to constantly validate one's own internal hypotheses:

- Explicitly state the hypotheses: Before looking at the data, disclose which causal relationships your management team considers to be ‘established’. Make implicit assumptions explicit so that they can be tested.

- Forensic validation and auditing: Use raw data analysis explicitly to falsify your mental models, rather than simply looking for confirmation of existing strategies. Look specifically for anomalies in attribute usage – a field that is used in the background for a dozen different processes is evidence of a false mental model.

- Acceptance of non-linearity: Replace the rigid ‘machine’ model with a dynamic ‘organism’ model. From a data perspective, deviations are not errors, but valuable signals about how your company actually works. Align your control mechanisms with the real sub-processes, not with the ideal.

- Symmetry of model and data (governance): Ensure that strategic planning and operational data collection are based on the same ontological foundation to avoid ‘semantic debt’. This requires rigid data governance and standardisation to prevent new process variants from diffusing uncontrollably into existing data structures.

- Reorganisation before innovation: Before investing in complex forecasting models, areas of poor data quality must be eliminated. This is not achieved through superficial data cleansing, but by unbundling the processes.

Conclusion

True leadership in the data age means having the humility to constantly correct one's own world view based on the objective hardness of the data. Those who ignore the divergence between their internal model and external reality are merely managing an illusion of control.

Today, the quality of a leader is measured by the speed with which they abandon a cherished management hypothesis as soon as the data contradicts it. Finally, ask yourself the question: Which of your strategic certainties would immediately collapse if you had to look at the raw, unaggregated data of your core process?

More articles on related topics:

Data Quality Management, Data Quality Dimensions, Data Profiling, Data Strategy, Data Quality, Operational Excellence

- Geändert am .

- Aufrufe: 229